Dangerous highways – a motorcyclist and bicyclist update

Posted on 23 September, 2021By: John Platts-Mills |

This article provides an update on three recent cases concerning the duty of highway authorities to “maintain the highway” and specifically their liability to motorcyclists and bicyclists, under section 41 of the Highways Act, 1980 (the “Act”). Whilst it goes without saying that accidents involving cyclists tend to result in higher value claims, they also require a more nuanced assessment of dangerousness than is often required in trip or slip cases brought pursuant to section 41 of the Act.

Nine lessons from the cases

- Claimants should take accurate and contemporaneous measurements of any alleged defect, a ruler should be used and photographed, failure to do so counted against the claimant in Nash.

- The existence, or absence, of a contemporaneous record of the claimant attributing the accident to a defect is likely to be significant, the absence of such a record counted against the claimant in Nash.

- Look to the contemporaneous accounts of investigators and lay witnesses, did they note or report a defect as giving them cause for concern? The absence of such a record counted against the claimant in O'Connor.

- Consider the location and context of the defect, is it something that might be encountered unexpectedly and when travelling at speed, cf. the defect in O'Connor.

- Investigate whether there are any relevant publications, in particular those published by the defendant, which might assist in establishing dangerousness, as was the case in Da Silva.

- If a defendant seeks to rely on the absence of the defect being: recorded by inspectors; reported by members of the public; or the cause of similar accidents - there may be explanations other than an inference that the defect was not dangerous - see Da Silva.

- Carefully consider any limitations on the claimant’s use of the road, the claimant in O'Connor struggled because the court found that the defect could be avoided by a motorcyclist. Perhaps the presence of overtaking traffic might explain a cyclist having to take a line towards the edge of a road where a defect was encountered. Alternatively, where a defect is encountered towards the middle of a road perhaps there is a justification for cycling defensively.

- Consider the particular vulnerabilities of the claimant and how they might interact with the relevant defect, the polished manhole cover in Da Silva posed a particular danger to Vespa drivers and provided a potential explanation as to the absence of similar accidents being reported.

- The absence of any record of the defect despite inspection is relevant but not determinative, a defendant would be wise to adduce evidence from its inspectors, see Da Silva.

Analysis of the three cases

The statutory provisions and the test of “dangerousness”

Section 41(1) of the Act, provides as follows: “The authority who are for the time being the Highway Authority for a highway maintainable at the public expense are under a duty … to maintain the highway.” Section 329 of the Act clarifies, if clarification was necessary, that “maintenance includes repair and “maintain” and “maintainable” are to be construed accordingly.”

To succeed under section 41 a claimant must satisfy a court, on balance of probabilities, that “the highway was in such a condition that it was dangerous to traffic or pedestrians in the sense that, in the ordinary course of human affairs, danger may reasonably have been anticipated from its continued use by the public” (Mills v Barnsley MBC (1992) PIQR P289).

It must be the sort of danger which an authority may reasonably be expected to guard against - there must be a reasonable balance between private and public interest (see James v Preseli Pembrokeshire DC [1992] PIQR 114).

Whether a highway is dangerous is a question of fact for the court. It is not a simple matter of measurement, although proper evidence of the dimensions of a defect is essential – see Walsh v Kirkless [2019] EWHC 492 (QB). Attempts to rely on parallels with decided cases are largely ineffective.

As to the circumstances: relevant factors include the location of the alleged defect and the use of the highway in issue. A pothole might be found to be dangerous in the context of a busy urban environment but not on a quiet country lane.

O’Connor v Luton BC [2021] EWHC 1691 (QB)

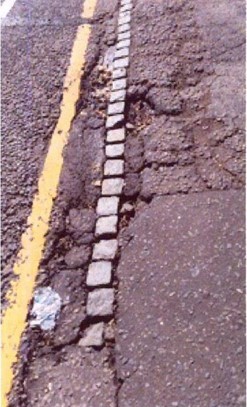

Whilst exiting a petrol station the claimant lost control of her motorbike and collided with a car. The claimant’s injuries were feared to be life-threatening: she had bleeding to her brain as well as a severely broken right arm, broken left arm, broken left leg and collapsed lung. Following the accident, the claimant’s children sent the highway authority photographs of a pothole said to have caused the claimant to lose control:

The highway authority immediately carried out temporary repairs, with more permanent repairs following in 2017 and 2018. The parties’ experts agreed that the pothole was about 200mm wide, 200-300mm long and 40-50mm deep.

The court heard evidence from a number of witnesses, including: two members of the motorbike club that the claimant was seeking to join-up with on exiting the petrol station; and a police officer who happened to be in the vicinity, PC O’Mahoney.

PC O’Mahoney’s evidence was that he did not recall seeing a defect that could have contributed to the accident. A similar view was reached by a representative of the Roads Policing Unit who attended shortly after the accident, his evidence was that: he “saw that there were some points where the tarmac had broken up close to the edge of the carriageway but did not consider these to be a potential contributory factor at the time”.

The court heard evidence from accident reconstruction experts and also experts in the handling of motorcycles. The judge found that as the claimant left the forecourt the rear wheel momentarily lost grip causing it to spin faster; when it regained traction the motorcycle lurched forwards; and whether because the Claimant’s hands were slightly cocked or because she instinctively gripped the handlebars harder, the throttle was increased significant (“whisky throttle”).

The claimant had no recollection of the accident, and her case that the loss of grip was attributable to a defect in the road depended upon the evidence of a member of her club. The court found his evidence unreliable, noting his failure to raise the pothole with the police at the scene or the local authority after the event. Accordingly, the claim failed for want of causation.

The court proceeded to consider the issue of dangerousness in any event. In concluding that the pothole was not dangerous, the court addressed the claimant’s use of the highway and the characteristics of use by motorcyclists generally.

It reasoned that whilst motorcycles are more vulnerable to defects than motorcars, they also have a greater choice as to which part of the road to use. The court distinguished between the defect in issue, which in the court’s view could be easily avoided and a defect in the middle of a carriageway, which a motorcyclist might encounter unexpectedly and when travelling at speed.

The court was also influenced by the fact that the investigating police officers had not identified a pothole as a potential cause, thereby indicating that “their experienced eyes did not regard the defects as dangerous”. Finally, the court noted the lack of complaints or reports about the defects.

Da Silva v Transport for London [2021] 4 WLUK 316

On 16 July 2016 at around 7 am, Mr Da Silva was on his way to work on his Vespa. As he navigated the junction of the northern section of Avenue Road and Adelaide Road in Swiss Cottage, he fell, breaking his left leg and his left wrist. His case was that it was the result of skidding on a smooth manhole cover.

In analysing the case, Recorder Jourdan QC sitting in the Central London County Court placed reliance on a number of documents including: the Highway Authorities & Utilities Committee Advice Note No 2012/02; and the LoHAC contract between TFL and CVU which identified the risk posed by worn or polished manholes. The claimant also relied on TFL’s Urban Motorcycle Design Handbook, which set out the particular vulnerability of motorcyclists to loss of control as a result of poor surface condition, including an indicative diagram showing a manhole cover just before a bend in the road.

The court concluded that given the location of the manhole cover, on the bend of a busy road approaching traffic lights, and bearing in mind the safety considerations identified in the three documents referred to above, the smooth condition of the cover was such as to render it dangerous and a breach of s.41.

It is of note that the court placed no weight on the fact that the manhole cover was replaced by BT within 24 hours of TFL serving notice on it to do so. However, the court did conclude that the language used by TFL in the s.81 notice did give some support to the claimant’s case (the fact that there was a polished cover in the carriageway had been entered in capital letters).

The defendant sought to place reliance on the absence of any record of the defect despite monthly inspection. The court was unpersuaded. It noted the failure to call evidence from any of the inspectors and the fact that of the 40 defects recorded none related to the surface of a mental manhole cover, tending to suggest that they were not made aware of the issue.

The defendant also sought to rely on the absence of other accidents or reported complaints, again, little weight was placed on it. The court noted that members of the public were unlikely to report issues with the highway on the basis of the number of complaints recorded by TFL.

In the court’s view the defendant’s strongest point was the absence of similar accidents. However, the court considered it likely that the state of the manhole cover was such that only motorcyclists driving motor scooters such as the Vespa, with small wheels, were likely to be adversely affected by the slipperiness of the surface.

Nash v Hertfordshire County Council [2020] EWHC 3247 (QB)

The claimant was out for a Sunday morning ride and cycling down a rural access road in Hertfordshire, as he rounded a 90 degree bend bounded by hedges he collided with a van travelling in the opposite direction. The claimant’s case was that a dangerous pothole had caused him to swerve.

The highway authority contended that whatever defects were present, they were not dangerous given their size and location. Its case was that the claimant was the sole cause of the accident in that he had cycled too fast and too wide around the corner – it relied on comments to that effect made by the claimant to a PC shortly after arriving at hospital, there was no record of him raising a concern about potholes.

The court noted that the potholes had not been measured with any precision by the claimant or his representatives, it was reliant on the experts who had done their best using the available film and photographs. The court heard evidence from a large number of individuals, both local residents and those involved in the investigation, which tended to indicate the presence of potholes, which were both covering a significant portion of the highway and significant in depth.

HHJ Lickley (sitting as a Judge of the High Court) was not satisfied that any of the defects were any more that 40mm. Furthermore, the defects were to the side of the road and allowed approximately two thirds of the road width to pass by them. Referring to the recent and well-known judgment of Walsh v Kirkless [2019] EWCH 492, the court concluded “there is simply not enough reliable evidence of the dimensions or conditions of the pothole for me to say it is more likely than not that it presented a real source of danger in the sense identified”.

An interesting feature of the analysis was that the judge seems to have considered that he could not be satisfied that a water-logged pothole was sufficiently deep to be dangerous from photographs, as the water in it made its depth indeterminable. It might be argued that a pothole full of water, however deep it may in fact be, might be dangerous to a cyclist in circumstances where they swerved to avoid it rather than test its depth.

John Platts-Mills has a busy Fast Track and Multi-Track practice. He is regularly in court arguing cases on behalf of vulnerable road users, including: motorcyclists, bicyclists and pedestrians. He manages this alongside the work he does as junior to senior members of Chambers on higher-value catastrophic cases.

Back to blog

Additional Information

All Blogs

Archive

- November, 2025

- May, 2025

- February, 2025

- January, 2025

- November, 2024

- September, 2024

- June, 2024

- April, 2024

- March, 2024

- December, 2023

- July, 2023

- May, 2023

- April, 2023

- March, 2023

- February, 2023

- May, 2022

- March, 2022

- February, 2022

- November, 2021

- October, 2021

- September, 2021

- August, 2021

- July, 2021

- June, 2021

- May, 2021

- March, 2021

- February, 2021

- November, 2020

- October, 2020

- September, 2020

- August, 2020

- June, 2020

- May, 2020

- April, 2020

- March, 2020

- February, 2020

- November, 2019

- October, 2019

- August, 2019

- July, 2019

- June, 2019

- May, 2019

- March, 2019

- February, 2019

- January, 2019

- December, 2018

- October, 2018

- September, 2018

- July, 2018

- June, 2018

- May, 2018

- April, 2018

- February, 2018

- December, 2017

- November, 2017

- October, 2017

- July, 2017

- June, 2017

- May, 2017

- April, 2017

- March, 2017

- February, 2017

- January, 2017

- June, 2016

- May, 2016

- April, 2016

- March, 2016

- February, 2016

- December, 2015

- November, 2015

- July, 2015

- March, 2015